Casa Morra

History and Project

Palazzo Cassano Ayerbo d’Aragona

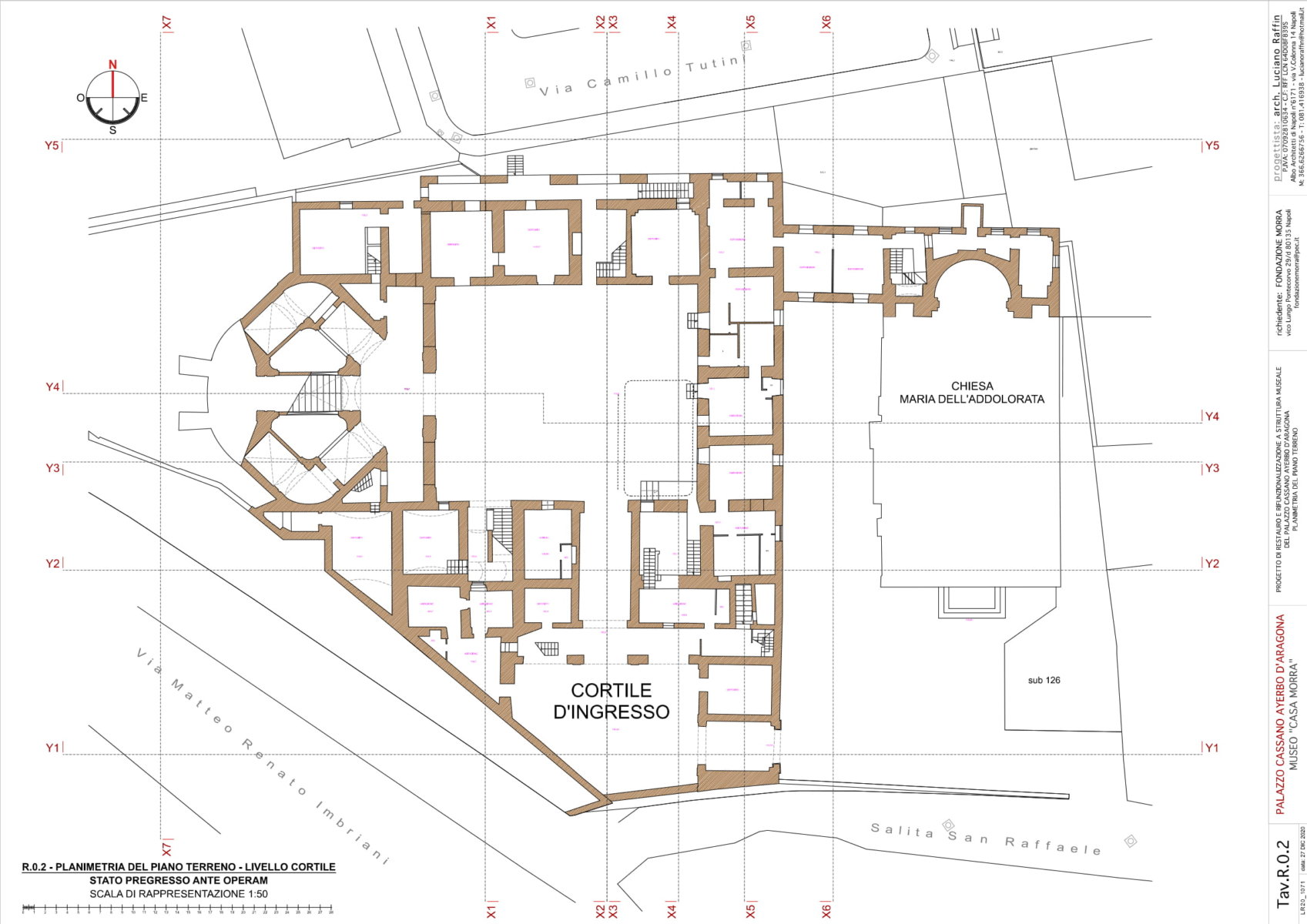

The building still shows, even today, the characteristic layout of the suburban villa seen in Lafrèry’s veduta of 1566. The original nucleus, faithfully depicted on the map, albeit with a different orientation to allow a better portrayal of the building, must have consisted in an entrance with a piperno ashlar portal situated on a steep rise, the building itself extending northwards from the entrance, with surrounding farm land, vegetable gardens and fruit trees. The portal opened directly onto a polygonal courtyard, whose irregular shape was dictated by the presence of a retaining wall marking the limit of the property along the roadside, and the body of the L-shaped building.

From a veduta by Alessandro Baratta just a century later (1629), we can note that the area had undergone an intensive urbanization process, resulting in the disappearance of most of the orchards and gardens, especially in the areas situated at the foot of the city walls. The farm building – owned by the Dukes Carafa di Bruzzano – has a fortified look due to the presence of a crenelated tower, and it is one of the few elements of continuity between the views of this area by Lafrery and Baratta, and it seems – as mentioned above – to have been completely transformed by a massive urbanization project.

Celano, writing in the late seventeenth century, described it as one of the ‘many fine lodges for the delight of the nobility’ and he informs us that it still belonged to the Carafa of Bruzzano family, while Parrino, in 1725, mentioned a hunting lodge in the San Efrem Nuovo area, but it now belonged to the Cassano Ayerbo d’Aragona family. The building must therefore have changed hands at the turn of the seventeenth century, when it ceased to be a hunting lodge and was transformed into a noble residence.

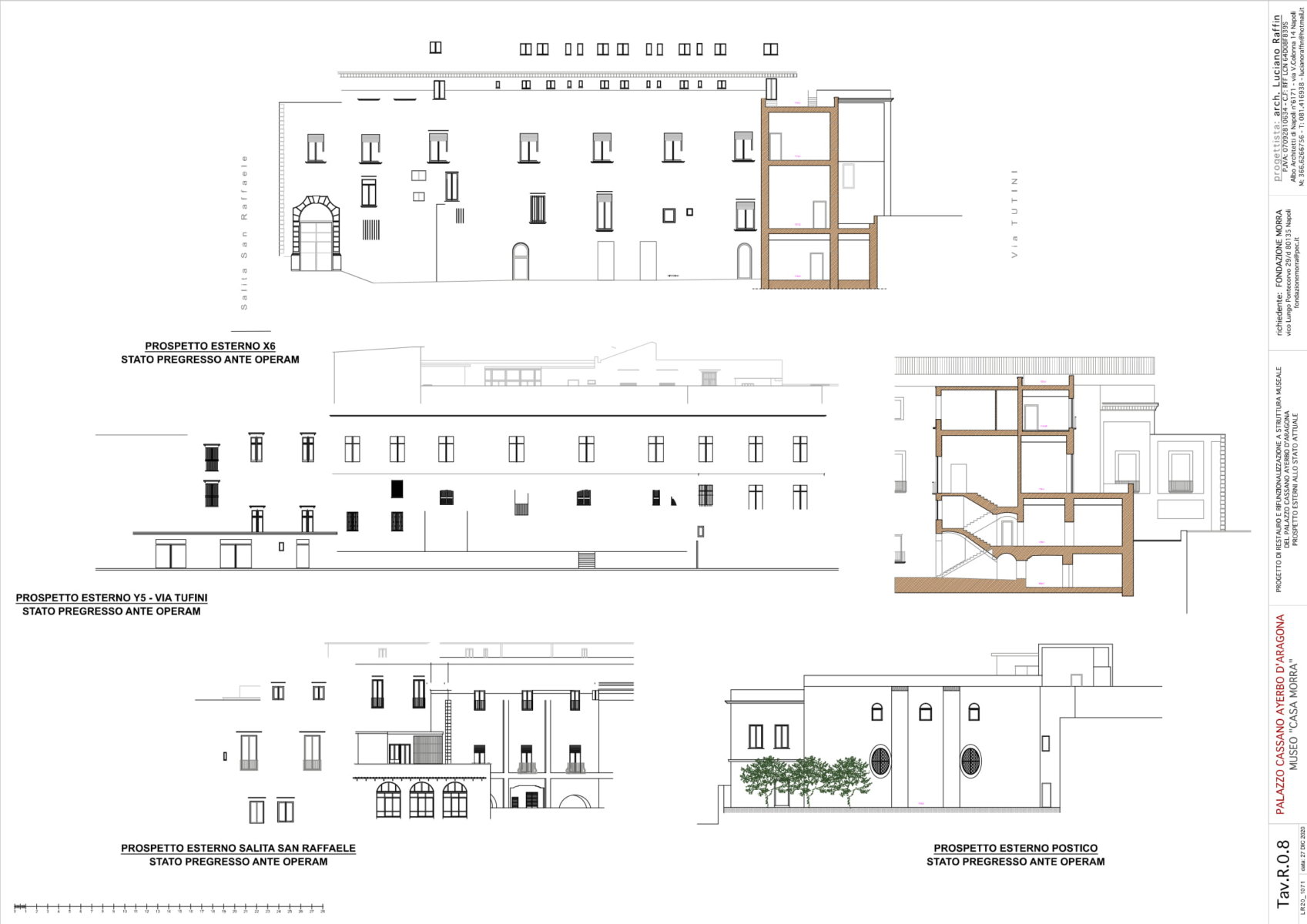

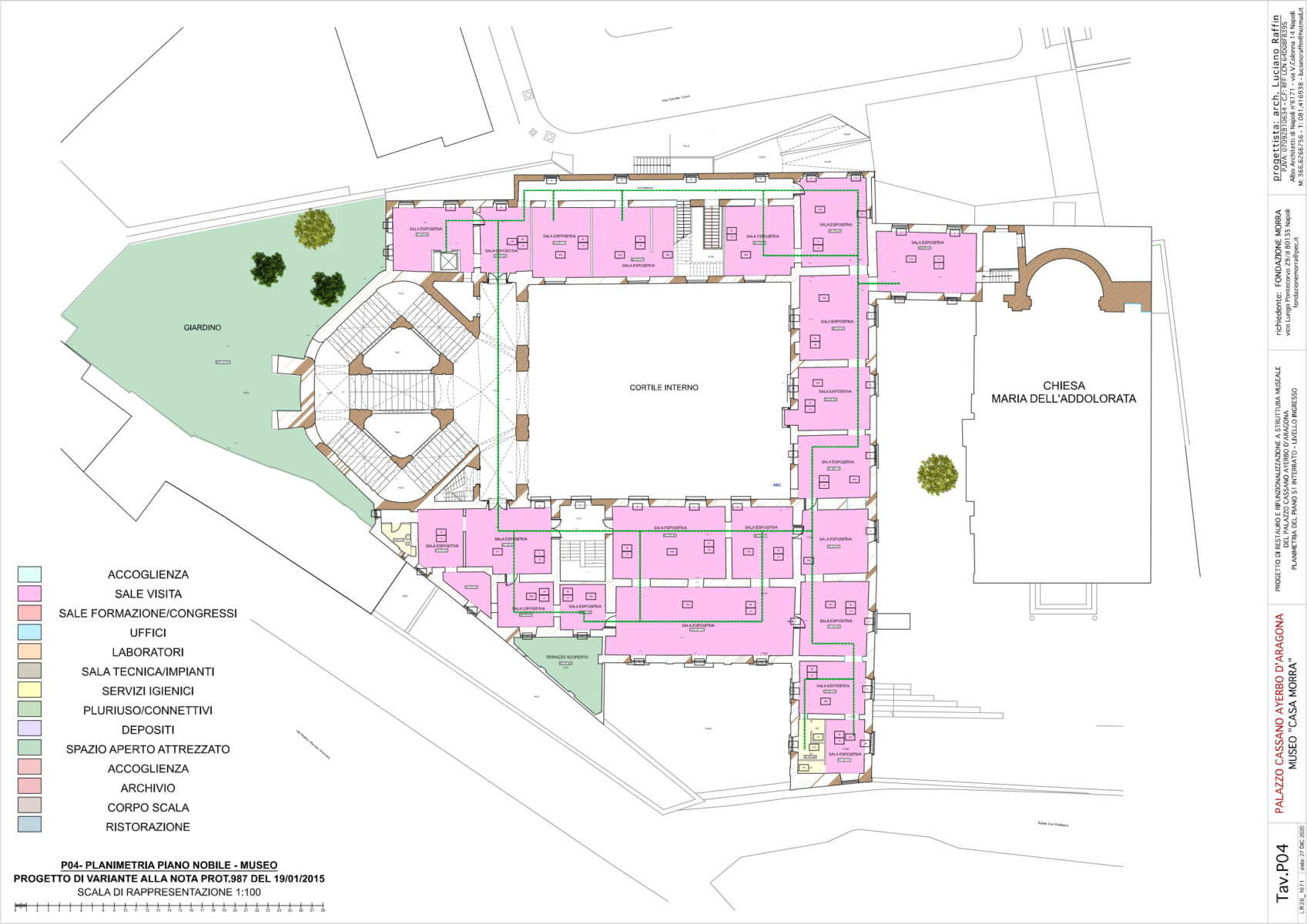

First mention of an enlargement to the building dates back to 1732, when a certain D. Giuseppe Cito was paid 39 ducats ‘for a number of ceilings, canvasses and their finishing and painting in the two rooms and chamber of the quarto nuovo del palazzo of the Prince of Cassano.’ Alongside the original nucleus consisting of the sixteenth-century farmhouse, the third decade of the eighteenth century saw the construction of a large rectangular courtyard around which the existing building extended to the south. The new buildings were arranged in a ‘C’-shape around the courtyard, leaving the fourth side open to the garden. The building must have been equipped with cisterns, as we know that in the year 1748 ‘water was drawn from them’ to be used in the construction of ‘walls, lamias, and arches for the new stairway’. Around the middle of the eighteenth century in fact a large octagonal monumental stairway was added on the side that opened onto the garden. It was first documented on the map of the Duke of Noja, whose topographic survey dates back to 1750. The staircase, with five flights of stairs, is rib-vaulted in tufa, resting on central pillars and side walls in blocks also in tufa. The first central flight leads to a composite landing, forming a central rectangle flanked by two arcs of a connecting circle, from which extend pairs of symmetrical staircases (with another landing) lead off to the upper floor.

After careful comparison with other exemplars, the stairway has been attributed to Ferdinando Sanfelice, creator of some of the most beautiful open stairways in Naples. In reality, one cannot speak here of a true ‘open staircase’ in the traditional sense, as it is framed by large segmental arches in the courtyard, which must originally have been an excellent source of light. The arcades, three per floor, are inserted into a set of cornices and pilasters with Tuscan capitals on the ground floor and Ionian ones on the upper floor. It is precisely this canonical superposition of orders that has led scholars to attribute the project to an architect schooled in the new cultural influences that were spreading in Naples after the arrival of Charles of Bourbon, and we may safely assume that the architect in question was Sanfelice himself.

The structure is completed by a composite decoration of geometric panels, designed by engineer Gaetano Barba, responsible for the restoration work carried out in 1785, which – according to archive documents – involved the stairway and the main buildings overlooking the rectangular courtyard.

In around the middle of the nineteenth century, the widow of the Prince of Cassano d’Aragona sold the whole property – villa, garden and estate – to the noble tertiary nun Maria Teresa de Conciliis, a devotee of Our Lady of Sorrows, who, in 1859, drew up a will in which she expressed the wish that upon her death ‘this building should be turned into a convent of the Servants of Mary’.

The Congregation of the Servants of Our Lady of Sorrows – founded in 1874, and incorporated in 1880 to the Servite Order, of which Sister Teresa de Conciliis was a member – probably already resided in the palazzo from the time of her death (1863), and actively collaborated in the construction of the Church of the Addolorata. The church as built next to the palazzo in the area originally meant for the garden and was certainly built before 1880, the year of publication of the Civic Map of Naples, where the church already appears.

The Sisters of Our Lady of Sorrows bought the entire property in 1906 and just two decades later sold the land – but not the palazzo and the church – to a cooperative called ‘Case Impiegati dello Stato’, whose purpose was to house public employees. This project led to the construction of the Rione Materdei district from 1925 to 1930.

Claudia Rusciano